This week, a clinical example of why clinical ignorance is not bliss.

All case vignettes incidentally, unless indicated otherwise, are hypothetical, pieced together from real interactions.

In this case Roger, a witty, well-groomed patient in his late twenties, occasionally had a hard time starting sessions. On those occasions he hemmed and hawed and said, “Not much to discuss this week, over to you!” Then a nervous chuckle, which set me on edge; no pal, that ain’t how this works.

I devised ways of handling this, the idea being that I cannot tell patients what to want or want to discuss. I offered statements such as, “Well, what’s on your mind?” (“Not much!”), or “So…what hurts?” (“Doing fine.”) or “What stayed with you from last time?” Crickets.

Roger would squirm, apologize for being difficult. I wondered if he was passive-aggressive, though his confusion and self-criticism sounded sincere.

Roger was confused about his orientation, identifying as “probably gay,” with occasional one-night stands with both men and women, often involving alcohol. We had much to discuss, yet he increasingly felt stuck, at the top of the therapeutic hour especially.

Was it shame that blocked him? “Maybe,” he responded, sounding helpless. “I wish I could say for sure.”

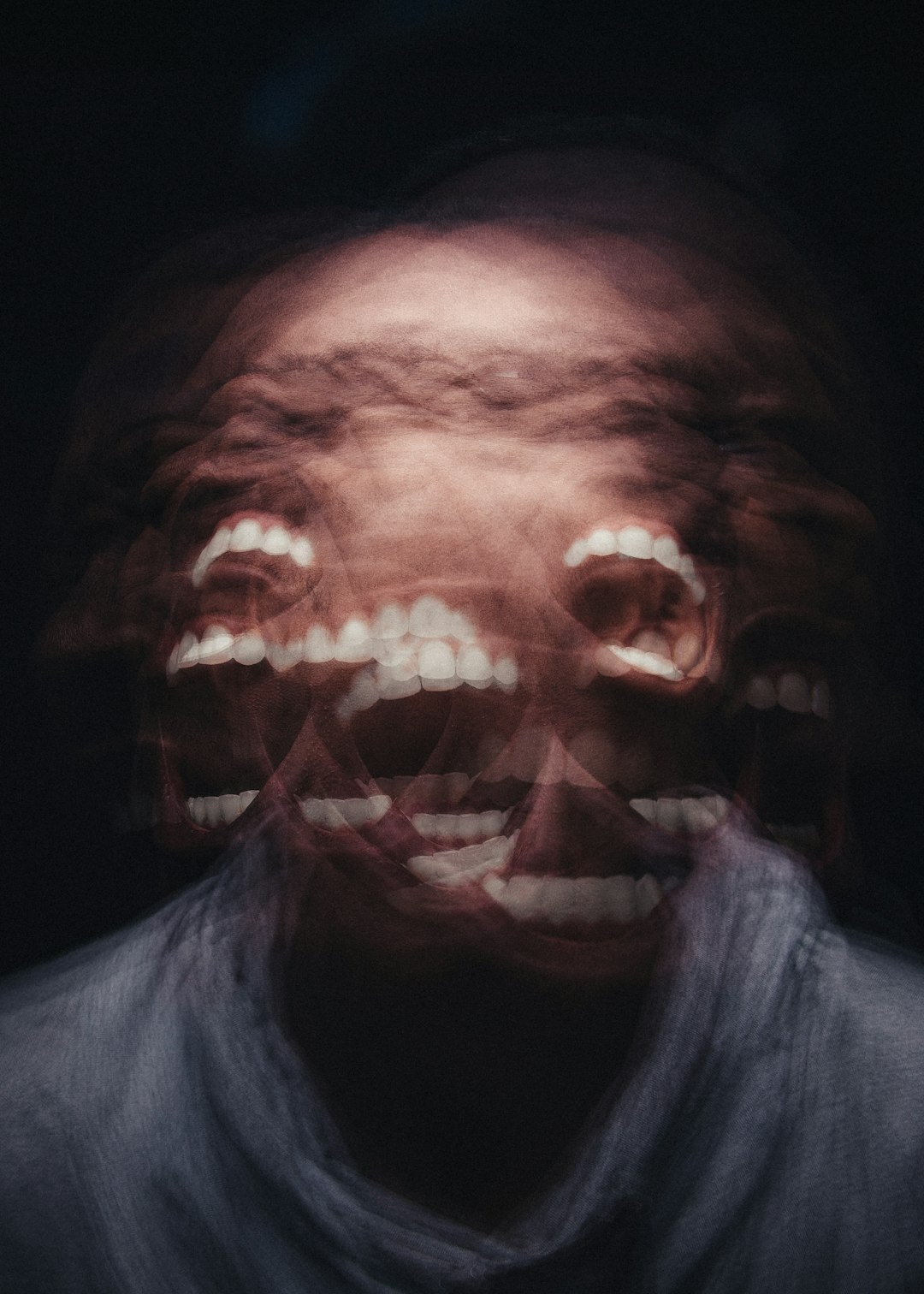

The great analyst W.R. Bion—a quick digression—encouraged newer analysts to think anew, stay freshly curious about why this moment, with this patient, is challenging. He astutely noticed the porousness between conscious and unconscious thought processes, subtle oscillations between neurosis and psychosis.

There was something vaguely psychotic about these fraught moments, two relatively smart guys tripping over themselves. You first, no you, after you I insist …. But often, even when I held the door for him, he balked.

Roger said he understood “the rules” of therapy, that the patient initiates a topic or theme. But knowing this did not help our cause, as I more frequently witnessed his paralysis and self-contempt. I began to quietly resent this; I did not mind prompting him some of the times this occurred, but he apologetically seemed to need it every time. Dude you’re not even trying.

One major clue, which I missed at first (under cloud of suspicion), was his comment that, “I’m just not sure how to do this.”

One day I pressed him harder than usual, hinting at my exasperation, leading to his irritable pushback: “Hey, I keep saying I don’t know why I’m stuck but you keep asking.”

I paused, struck by the strained parent/child dynamic I had heard. I said, “Maybe you…need more help?”

He said, “Sorry, I know it’s pathetic.”

“Or maybe it’s hard to ask, given your history.”

He exclaimed, “Understatement of the year!” and we both laughed.

In many ways I related to Roger’s wariness, a fear of “bothering” others with his needs, as therapy felt self-indulgent to him. He wanted what wasn’t allowed, historically: an emotional space and mind of his own.

This was my past as well; it sometimes felt Roger overburdened me with responsibility, provoking an old resentment which beclouded my sending his anxious shame.

I feared I too handled things poorly, as various approaches faltered. There was also a fear of being jerked around, forced to dance to his tune, as I had with my own father many years before.

In this way Roger and I were both tongue-tied, with the sneaky dread of being seen as inadequate, given our parallel childhood demands to be precocious.

The sporadic limbo of sessions characterized Roger’s life; he needed me to show keen interest to grease the wheels, make it safe, encourage and allow him to want a selfhood of his own.

His father, a soccer coach at a Catholic high school, was cordial but distant, a rift exacerbated by Roger’s disinterest in sports and action movies. This distance increased after his parents’ divorce, when Roger was in high school. Roger talked about the difficulties his parents went through.

His father soon remarried, leaving Roger with his anxiously dependent mother, who struggled with a rare immune disorder that worsened and left her bedridden. The caregiving fell to Roger, his dad remarking that “she’s your problem now.”

His mother turned him into a surrogate “buddy,” undermining his autonomy via accusations of selfishness, which crushed him. She subtly demanded he stay by her side; in a way he was still there.

There was also the fear his therapist would abandon him; his previous one had abruptly retired. Or that he might develop feelings for me, which might make me uncomfortable, jeopardizing the relationship.

He also experienced me as intrusive when I peppered him with questions, a sign of my anxiety to handle things correctly. Mom too used to grill him, with caustic jibes, until he cancelled his plans and stayed home.

Roger’s “caginess” was survival; for him to proceed more directly was a dire risk. It was so difficult to determine and say what he needed.

The more I understood all this, the more fluid things became. Eventually Roger asked me for help in shortening his mother’s frequent, rambling calls; he also confronted his father on the latter’s disinterest and semi-homophobia. This provoked his intense guilt, often (ironically) a sign of progress. I was proud of him, which he recognized.

Pursuing his hopes and desires brought profound anxiety. This prompted anxiety of my own, as I misread his paralysis as a way of seizing control, a binding either/or of who was responsible, crowding out a deeper curiosity of his stuckness. This was underlined for me when Roger one day exclaimed his frustration with his folks, namely that, “Why can’t they just, you know, parent!” They did or could not, leaving him with a rage he had to swallow, sometimes with shots of tequila.

This dilemma became ours, our mutual angst preventing language games of intimacy that I until my own therapy did not know how to play—a small example of how the therapist, too, takes the journey.

Thoughtful insights that had never occurred to me, as a non-therapist. Am torn between wanting to reassure you that you were successful as a therapist and letting the results (the patient ultimately confronting his parents) speak for themselves. Nice article.

I could not help feeling how much his hesitation to approach you, to love you mirrored his hesitation to approach & love men. "Confused about his orientation", "I'm just not sure how to do this", "He wanted what wasn't allowed, historically". What a lovely case.