Ducking the issue

How noxious systems manipulate our need for magic and misdirection

First of all happy holidays, and welcome new subscribers! You have no idea how inspiring it is when someone new signs up to get these posts, so thanks. And now to the latest installment, on oppressive family or caregiver systems and their suppression of our natural need for enchantment.

Noxious systems manipulate our human need for magic, for instance a family ruled by narcissistic or compulsive demands to prioritize the needs and protection of caregivers. What is magically “produced” here is the not any useful enchantment but the illusion of certainty, at the cost of the perceptual and emotional reality of the vulnerable. Thus the child’s credo becomes, to a pathological degree, “believe what I’m told, speak and think as I’m expected, and I’ll be safe.”

This is of course especially true of children, or the child-like aspects of vulnerable adults, with their organic (I believe) need to believe in transformation: the discovering of the new via the child’s own exploration and play. This includes hide and seek, and the joy of animating objects in transitional space, puppets and teddy bears come to life. In the peekaboo game, the child “discovers” the joy of the lost now found, the transformative reversal of disaster.

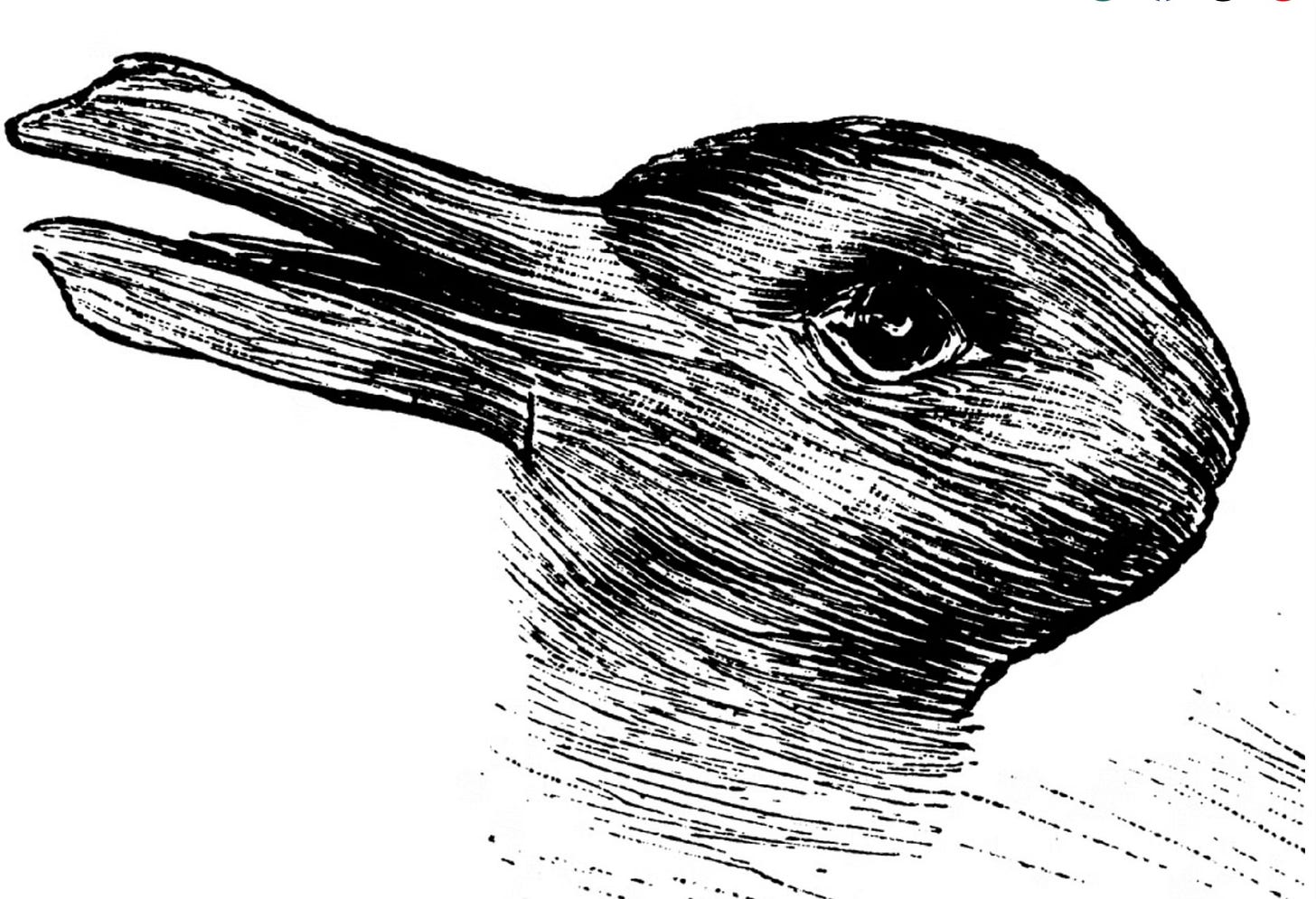

Likewise the child discovers (as I myself took joy in discovering) optical illusions, the aha moment of seeing the duck in addition to the rabbit, this single image of two (referred to technically as “Jastrow’s illusion”).

An oppressive system, however, insists on only the duck, the rabbit made invisible or inconsequential. Like a caregiver or parental couple denying the impact of their obvious anger or alcohol problems: “It’s not that bad, you’re exaggerating, at least you’re not starving like kids in poor countries….”

In this way the perceptual reality of the child, or the more vulnerable, is continually denied and called into question, the plainly visible in doubt, illusory magic quashed—at least in the family or system’s public places. (In other word, such need goes inward: fine breeding ground for addiction, where substances provide transformations not found in said public spaces—magically tangible, immediate, and off the radar.)

Such authoritative certainty erases the ambiguity of change (who is causing what), which we need to believe to make life tolerable. As a kid it was remarkable that such images changed before my eyes; now a duck, now a rabbit…now a vase, now two faces…I loved James Bond and Indiana Jones, in contrast to the ugly reality of warring parents who were tone deaf to their children.

Winnicott highlights the paradox, itself a source of illusion, namely the caregiver-child or therapist-patient pairing: one unit or relationship compromised of two. This of course becomes analogous to the rabbit/duck. In authoritarianism there is only one, as the caregiver/leader declares that they alone can fix it. One ruler, one answer, eroding ambiguity and the need for compromise constitutive of more “disorderly” democratic systems. But a rigidly imposed unitary definition is a disorder of its own.

It is for the most part impossible to see a duck and a rabbit at once, a vase and two faces together—much as we foreground a child or patient’s perspective under the background guidance of the caregiver/therapist. We speak and read one word at a time, left to right, moment to moment, per the successive single ticks of a clock (as if time were literally measurable.) But in the aridity of oppression, only a ticking realism counts as reliable.

The in-betweenness of the therapy, both a pairing and a separation, that potential space, fuels its transformative power; as Winnicott noted, such in-betweenness includes the imagination and fantasy of the child and the tangibility of the puppet or toy “come to life”, with movies and cartoons often more real than reality.

During a recent visit to Disneyland, the “magic kingdom,” I realized the silly or dopey (as it were) costumes worn by paid staff were not magical unto themselves, but rather as a receiver of a child’s projected fantasy and desire for such animated reality, including the nostalgia or vicarious pleasure of adults: a heightened parallel to the ordinary magic of human relatedness, given our pleasure in hearing stories read or told to us at bedtime by parents, grandparents, teachers, and so on. (I’ll never forget the Czech fairy tales told to me by my grandmother, in that rolling Czech accent.)

Winnicott insisted on the clinical importance of play. It is easy to take this literally, or wonder what he meant analogously. He means, in my reading, the very in-betweenness of real and imagined, possible and tangible, the joyful freedom of invention and spontaneity, within a safe-enough intersubjective ambience.

There is a sadness now, in thinking of how much joy I found in the illusions above, or in the joy of playing with my siblings, making up stories with our puppets, bringing our dolls to life. “Why are you pretending they’re real?” my parents sometimes asked, puzzled beyond reach of us, given the reality of the addictive adulthoods to follow.

Relatedness itself is an in-between, the transitional overlap or intersubjective space elusive to definition. Binaries freeze-dry such ambiguity into arid obviousness; Winnicott warns analysts not to control or coerce the patient (as with a child) in order to appease whatever anxiety they (the therapist) are facing, destroying the needed illusion, where a patient discovers something surprising behind the couch—their own value, for instance, which we have had eyes on from the start.

Winnicott insisted that patients like children make their own discoveries, operate independently rather than feel overly guided or nudged towards “correct” answers or perceptions (as in the noxious false-self systems he dreaded and witnessed constantly).

Of course this independence is somewhat illusory, nurtured within the ambience of an actual home (or therapist’s office): a relational home (as Stolorow calls it) emerging within a pre-established structure. Within the walls, hard reality loses its stickiness, fluctuating with the imagined, unless it is crushed by the “anti-illusion” of control or coercion.

Poisonous relational systems in other words stay “sticky” via their insistence on a tangibility defined unilaterally, suffocating the in-between. History is airbrushed to favor the rulers, with quieter perspectives painted out of existence (leading in some cases to the need for loud rebellion or resistance.)

This destroys the fragile need for transformative magic that occurs in variegated ways across the lifespan. It may be Sesame Street or Disney for a child, or for an adult the movements of music, movies, nature, good food, sex, or falling in love. (Isn’t sex the ultimate procreative magic, made “anti-illusory” with over-reliance on its intoxications?)

Certain aspects of parenting are magical (when not exhausting); when I first met my daughter, I was stunned by the generative power of nature herself, manifesting in this tiny creature sucking on air, in search of a breast: embodied vulnerability in action, strong yet centrally tender.

As it was with early Spielberg films, which as a child touched my need for adventure and escape: “Jaws,” “Close Encounters,” and Indiana Jones were even more potent because of the roughness of the real (i.e., family life.)

A corroding caregiving system turns child-like in-betweenness to rot, in making it concrete, literal. Why are you pretending it’s real? Gone is ambiguity; there is only a duck, and saying you see a rabbit means something shameful.

In this way the child’s mental reality is drained of vitality, damaging their ability to make their own way in the world—existentially, agentically—because the individualized meaning-system, nurtured in embryonic safety, is ever overshadowed.

Much of said oppression occurs under the guise of the rational—what can be logically proved or literally shown. The rational, or its rebellious opposite, always has the last word; everyone in such a system is always living in the shadow of the Berlin Wall.

What is lost here is the ability to enjoy the illusions of so-called reality itself. Magic follows us well into adulthood, in ordinary relations and even in our language. One of our greatest illusions is the notion of transcending all illusion via our intelligence, with an overemphasized faith on (for instance) science, medicine, technology, or even psychoanalysis.

Language is bewitching in this regard (as Wittgenstein often noted); we imagine we know what is meant by “time” or “the present,” as if a watch or calendar “shows” time, the second hand marking the flow. These among other things (the denial of our mortality, the strengths of our favorite candidate) are illusions we cannot always live without. Taken to extreme, the compulsion to master or “understand” all things tangible destroys all mystery, draining the life from imagination. (Who loves a know-it-all?)

Our endearing fallibility consists of the impossible tightrope between the imagined and the real, the possible and the tangible; oppressive control, imposed or self-perpetuated, robs us of our necessary stumbling, our quixotic journeying towards planned accidents (or accidental structures). Voters demand that the president know how to curb inflation, keep their nation invulnerable, to know solutions for everything. Powerful interests expect results from scientists, teachers, and artists. Even therapists need to know a treatment is “going somewhere good.” Perhaps it is this grasping that, in the end, proves the most seductive compulsion of all.