A few years ago I published a brief article about patient “Debbie,” who began asking yes or no questions about whether Kendrick Lamar was covertly communicating with her via social media.

At the time I could not answer, of course, while still directly wanting to, an anxiety that was quasi-paralyzing. I have come to understand this better.

It all started when Debbie told me Lamar had “liked” her comment on one of his social media posts, in which he extolled the benefit of living clean and sober.

Debbie had been sober for two years. In the comments she posted a thank you and celebrated her recent anniversary in Marijuana Anonymous. This comment received a “like” from the man himself. Debbie was ecstatic.

The next day he posted a comment that warned about celebrating drugs in music, including marijuana. Was this a shout-out to Debbie?

She talked about nothing else, wondering if this indicated Lamar’s romantic interest (sic.) I felt inadequate in not knowing how to respond to the question without dashing her dreams, uneasy that said dreams led to the conviction of some concrete answer. Was this borderline psychosis, a long term effect of marijuana and ‘shrooms?

In a way the answer was yes—given the psychotic cruelty of her upbringing. Debbie, mid-30s, was bi-racial and differently abled, partially paralyzed on one side due to birth complications. Her father was Asian and her mother South American.

Debbie was bullied in grade school, due to her stiff gait, partial hearing loss, and an occasional stutter; all of this, including the bullying, warranted further verbal and physical abuse from her father, who called her a loser for being bullied. Her dad loudly and repeatedly favored her younger brother: patriarchy on steroids.

Her mother remained passive, afraid of her husband, leaving Debbie on her own, even when she was locked in a dark closet overnight without food, water, or bathroom access. Her crime was making mistakes on her homework, due undoubtedly to terror of “messing up. “I came to expect the worst,” she told me.

Debbie responded favorably when I validated the emotional hell of all this, how marijuana was a wonder drug at first; finally life was tolerable, in color, funny! (She had a wonderful wit.)

But now, well into her sobriety, she wondered if social media was an addiction. I said it could be, potentially. (An answer I now question.)

Debbie earned a good living as a programmer, working remotely. This gave her ample space to spiral down the rabbit hole of internet news and celebrity gossip, to wonder if certain male stars’ “likes” indicated friendly or even romantic interest.

She talked of trying to meet Lamar backstage at a concert; surely he would remember her. Perhaps she could wait outside his dressing room, slip him a love letter.

Rather than accepting these fantasies as real or not, I saw them as dreams, real in their psychic existence, Freudian wish fulfillment (in part)—correctives against the bottomless pain of harrowing neglect.

Her fantasies after all had rescued her during those endless nights in the closet, including when, she plainly told me, her dad threatened to let her die in there. Would anyone notice? (Eventually she tucked away a flashlight, books, bottled water, and a large basin. Self-sufficiency became her religion out of necessity.)

She dreamed of having one of the loving fathers she saw on TV. Later, marijuana added color and boost to these aching fantasies of the loving experiences cruelly denied her.

Her fantasies were protective, in other words, of core desire, the goodness of her longings rather than their “selfishness”: a longing for safe recognition of basic relational nutrients, including validation, now expressible only (in her world, given its limitations) in these particular forms. Better for longings to exist in such forms than not at all, even if they remained somewhat in the closet.

I now read her yes/no questions as, Am I crazy for wanting this? The answer of course is no. Debbie was hungry for intervention against her father’s ongoing psychic presence, the internalized shaming voice, echoing the violent starvation of love and recognition—which she feared, at the worst of times, she truly deserved. (Abused kids need to do this, to make sense of the world.)

She needed the life-saving breast, to put it primitively, denied via her mother’s constant withdrawal and self-protection. It was classic caregiver self-interest, projected upon the child, who internalized said projection to survive.

In part what “normal” caregivers provide is a validation of a child’s basic needs, as being something good rather than selfish, welcome rather than demanding from others or even hurtful: a common terror among parentified or traumatized children, who often fear overwhelming others.

In therapy this may present as “resistance” but often turns out to be a protection of the relationship, from an impoverished patient’s point of view.

The denial of the goodness of our soulful need, the shaming of core relationality, can lead to imprisoning self-doubt of our own senses, even of our emotional sanity.

For Debbie, dealing with actual men was dangerous. She was terrified of rejection (a post-traumatic reaction), agonizing over whether her male friends from recovery had any actual interest in her. Or was she crazy?

It was probably the latter, so why not do the crazy thing in seeking love from Kendrick Lamar? The verdict had long been in.

Only recently did I remember some of my own psychotically-withheld need, in the context of an alcoholic upbringing. This led to my own reluctance to pause to understand Debbie’s questions at depth, rather than try to answer yes or no.

First we have my own freeze in the face of yes/no questions, reminiscent of that game of my father’s wherein he showed off by humiliating others via true or false “quizzes” on current events.

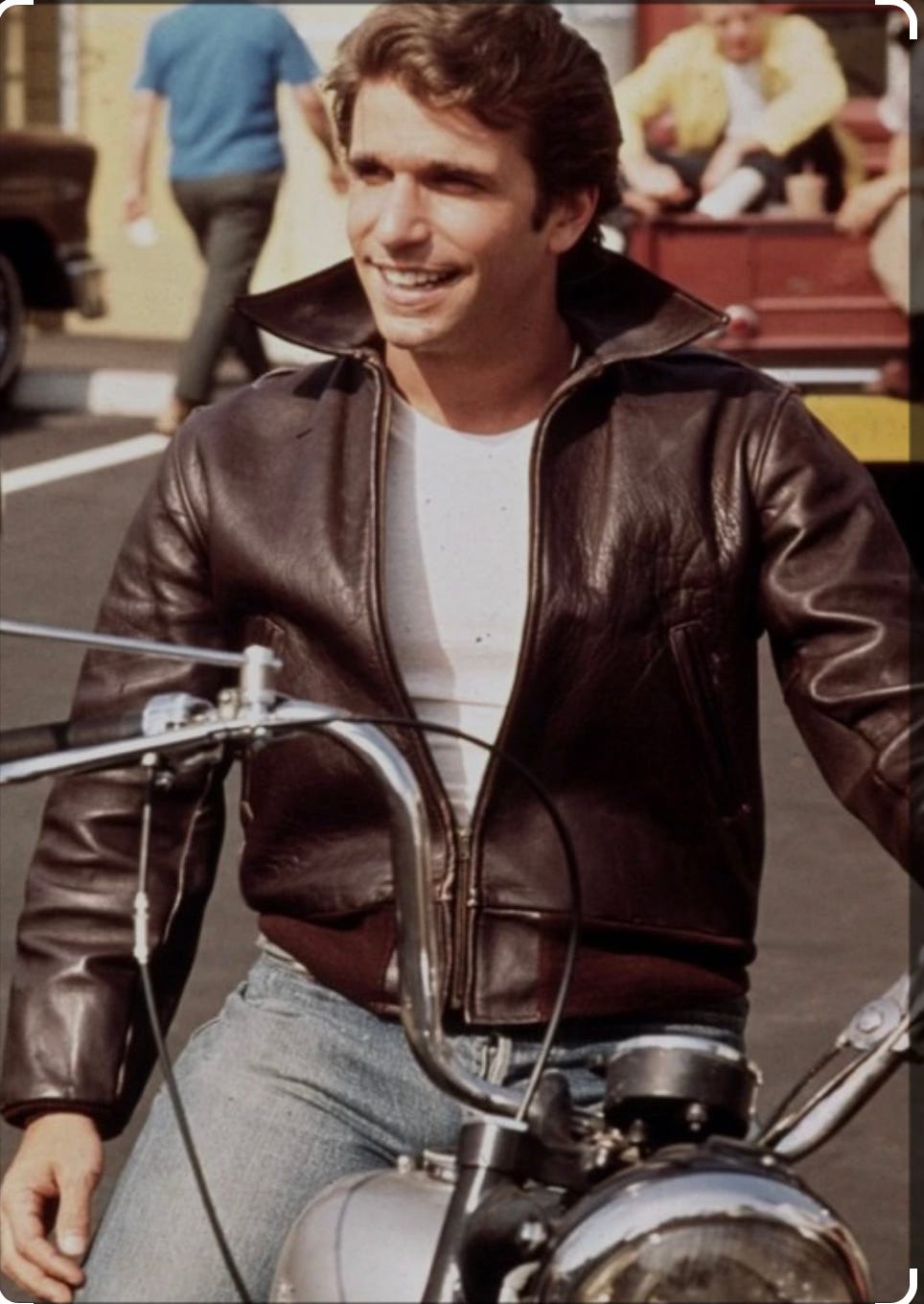

I also, while presenting this case during a lecture, spontaneously remembered loving the show “Happy Days,” and how I decided one day, in my nine-year-old wisdom, to write to Fonzie (younger readers please Google) care/of the ABC network. I was convinced that the Fonz would get my letter, see that I was cool, and take me on the back of his motorcycle to the movies. Surely he too loved James Bond. Heyyyyy!

I made the mistake of confiding to a friend about this, and was teased mercilessly for weeks. “Haber thinks he’s friends with Fonzie!” (As if being short and four-eyed wasn’t enough.).

I had to protect these fantasies at home too, since like most narcissists my dad might have taken offense and mocked them into the ground, since his son possibly revered someone besides him. I recall that Debbie’s father discouraged or actively sabotaged any interest in boys as she got older. (This was I think behind her insistence in asking me the yes/no questions. Could I tolerate her attraction to another man?)

The two of us were like siblings in the narcissistic paternal transference. I began eventually to see myself as the protector of her imagination.

That’s the nice part. More difficult was immersing myself in Debbie’s emotional world, revisiting the pain of immeasurable abandonment, a world more dangerous than my own: a crime scene of sorts, the destruction of a psyche, wherein one’s very thoughts, wants, and needs were profoundly threatened. Both of us avoided “going there” in different ways.

What I recognize now, even more than the first time I wrote about this, is that Debbie needed someone to go there with her—this after all was an aspect of her fantasy with Lamar, that he might reach out through the screen like the Prince at the ball. (The clock was always striking midnight.)

What was most real for Debbie, and for the young boy writing to Fonzie, was the relational craving that lie behind the seeking. Such invisibility or lack of recognition concretized the action itself. I was terribly disappointed when Fonzie (played by a humble Jew, it turns out) did not respond.

Eventually I initiated a more playful approach to Debbie’s yes or no questions, instead wondering what she thought Lamar might be thinking, the interest he might take in her. She’s sober, how cool!

This loosened things up between us; the more she could play with the outcomes, in our co-created transitional space, the less she needed the yes or no, and the more she saw how little control and responsibility she had for others’ choices.

In other words we drew away from constricting literalism, closer to the world of myth and folk tale, the personally symbolic, with its overwhelming gravitas; finally she got to play at being Cinderella with a supportive male, interactions wherein I validated the goodness and poetry of her longings—tragically unmet, albeit as sacredly real as any connective mythology or narrative echoing the soulful strivings in all of us.

Which also, as I will explore later, even draws some of us to be psychoanalysts.

So does this mean my future gay very married with children husband Matt Bomer is a bad thing?